Injury specialist, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at the latest study about concussion in sports, especially regarding early/on-field assessment and diagnosis of this condition.

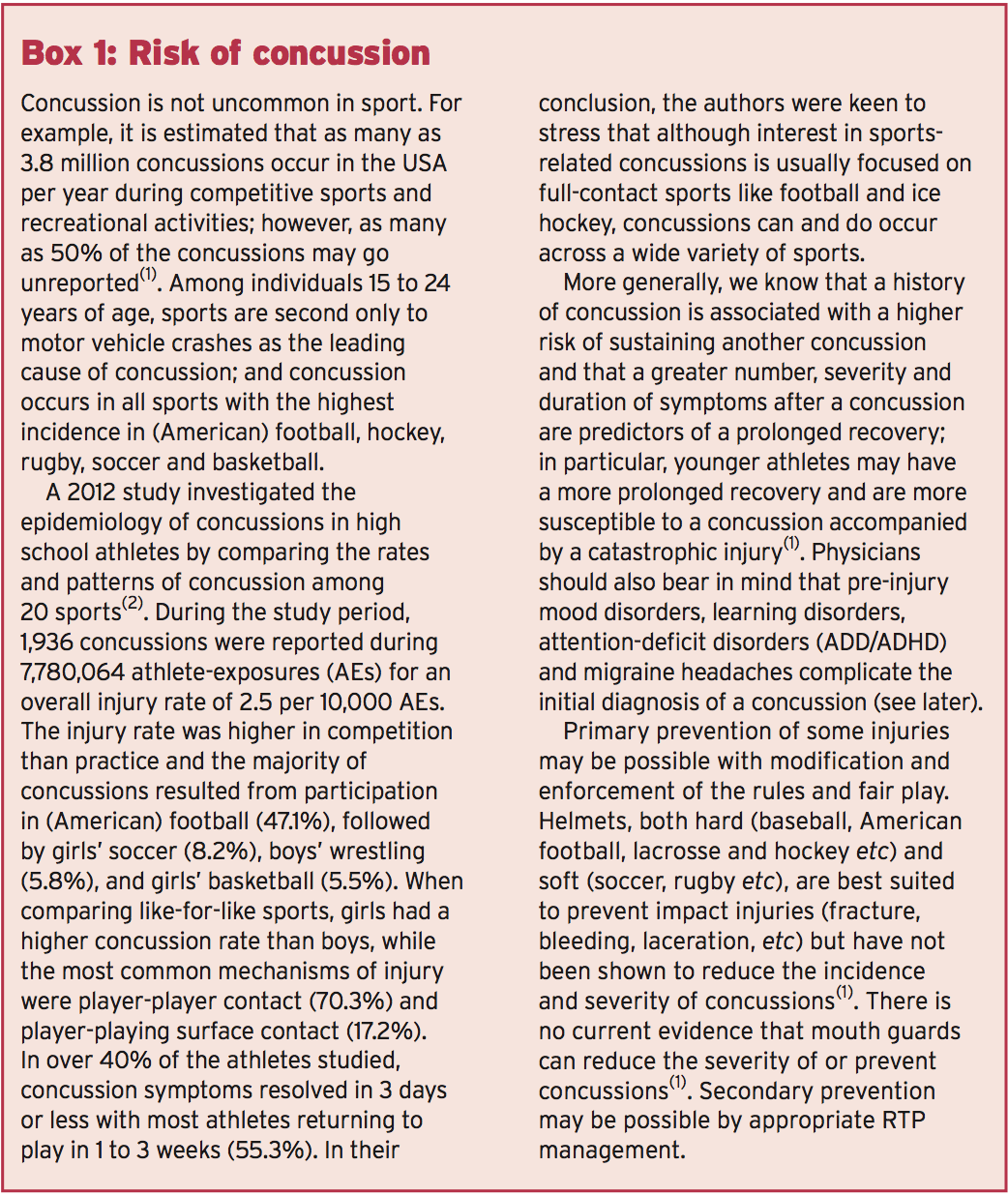

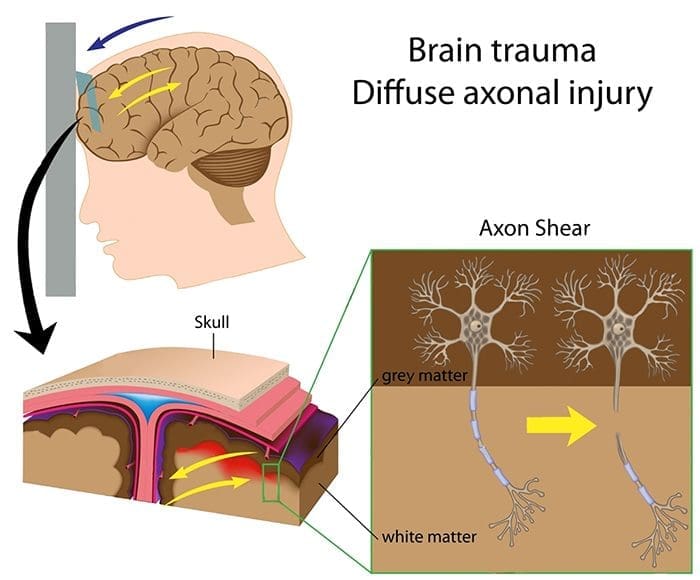

The proper medical definition of concussion is: a clinical syndrome characterized by immediate and transient change in brain function, including alteration of mental illness and level of consciousness, resulting from mechanical pressure or injury. But, it is more commonly described as an injury to the brain caused by a blow to the head (eg an uppercut in boxing, a clash of heads in soccer or a fisherman moving over the handlebars on the ground etc), which leads to temporary loss of normal brain function, including disturbances in memory, judgment, reflexes, speech, balance and muscle coordination. A less obvious cause is an indirect blow where the force is transmitted up to the head from a different portion of the body — for example when a stationary rugby player is tackled from behind causing his head to abruptly flick back, with a number of the force of the tackle passing through his brain; the participant may end up concussed without ever taking a direct blow to the head.

While bruises and cuts might be present on your face or head as a consequence of this blow, in most cases a person with a concussion never loses consciousness. Because of this, less experienced coaches and sports physicians may not immediately assume concussion, or if they do they presume that it’s unlikely to be a cause for concern. But, though some concussions are less severe than others, there’s absolutely no such thing as a ‘minor concussion’; while a single concussion should not result in permanent damage, another concussion shortly after the initial one doesn’t have to be very powerful for its consequences to be fatal or permanently disabling. Animal and human studies support the concept of this so-called ‘post-concussive vulnerability’, showing that a second blow before the mind has regained results in worsening metabolic changes within the cell(1). This explains the crucial importance of correctly and immediately identifying when a concussion has occurred because it affords the opportunity of this athlete to be taken out of the field of play, thereby ensuring a second concussion cannot happen.

Table of Contents

Initial Diagnosis Of Concussion

As soon as an athlete suffers a blow to the head, the first priority should be that someone qualified is available to assess whether concussion has occurred. In an ideal world, this assessment could always be performed by a physician specifically trained in this area. In many sporting events (eg a small league football game), it is unlikely that such a individual will be there standing on the sidelines. However, as stated by the America Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), the competence to execute this assessment also needs to be decided by training and experience and not purely dictated by specialty(1). To put it differently, with the right training and expertise, coaches, trainers and health care professionals are more than capable to perform a concussion examination.

The AMSSM additionally points out that the identification of concussion is ideally created by a healthcare provider who is not only knowledgeable in the recognition and analysis of concussion but also familiar with the person concerned. The reason for this is that while standardized sideline tests are a useful framework for making an appraisal, the validity and reliability of these tests are greatly reduced without some type of individual baseline test result with which to compare, and some other baseline rating will vary based on the individual athlete concerned.

AMSSM New Guidelines

AMSSM New Guidelines

The primary recommendations were assembled by reviewing the evidence over a number of years and are summarized as follows:

- Any athlete suspected of having a concussion should be stopped from playing and assessed by a qualified healthcare provider trained in the evaluation and management of concussion and ideally someone who is familiar with the athlete (for the reasons given above). The recognition and initial assessment of a concussion should be guided by a symptoms checklist, cognitive evaluation (which should include orientation, past and immediate memory, new learning and concentration), balance tests and further neurological and physical examination.

- Coaches/physicians/healthcare providers should take note that while balance disturbance is a specific indication of a concussion, it isn’t very sensitive. In particular, performing equilibrium testing about the touchline may yield substantially different results than baseline evaluations simply because of differences in shoe/cleat-type or surface, use of ankle tape or braces, or the presence of other lower extremity injuries that might have also happened during the episode involving the head injury.

-

Any athlete suspected or diagnosed with a concussion should be monitored for deteriorating physical or mental status. Importantly, there should be NO same day return to play for an athlete diagnosed with a concussion injury. Meanwhile, imaging should be reserved for athletes where intracerebral bleeding is suspected.

- Even though most concussions can be managed appropriately without the use of neuropsychological (NP) testing, those with athletes in their maintenance ought to bear in mind that NP evaluations are an objective measure of brain- behavior relationships and, as such, are somewhat more sensitive for subtle cognitive impairment than a straightforward clinical examination. However, NP testing should be used only as part of a extensive concussion management plan and should not be utilized in isolation. Also, the ideal timing, frequency and type of NP testing have not been completely ascertained.

- Computerized NP testing should be translated by health care professionals educated and comfortable with the type of test and also the individual test limitations. Paper and pencil NP evaluations are both valuable and are able to test different domain names and assess for different conditions, which may masquerade as or reevaluate evaluation of concussion.

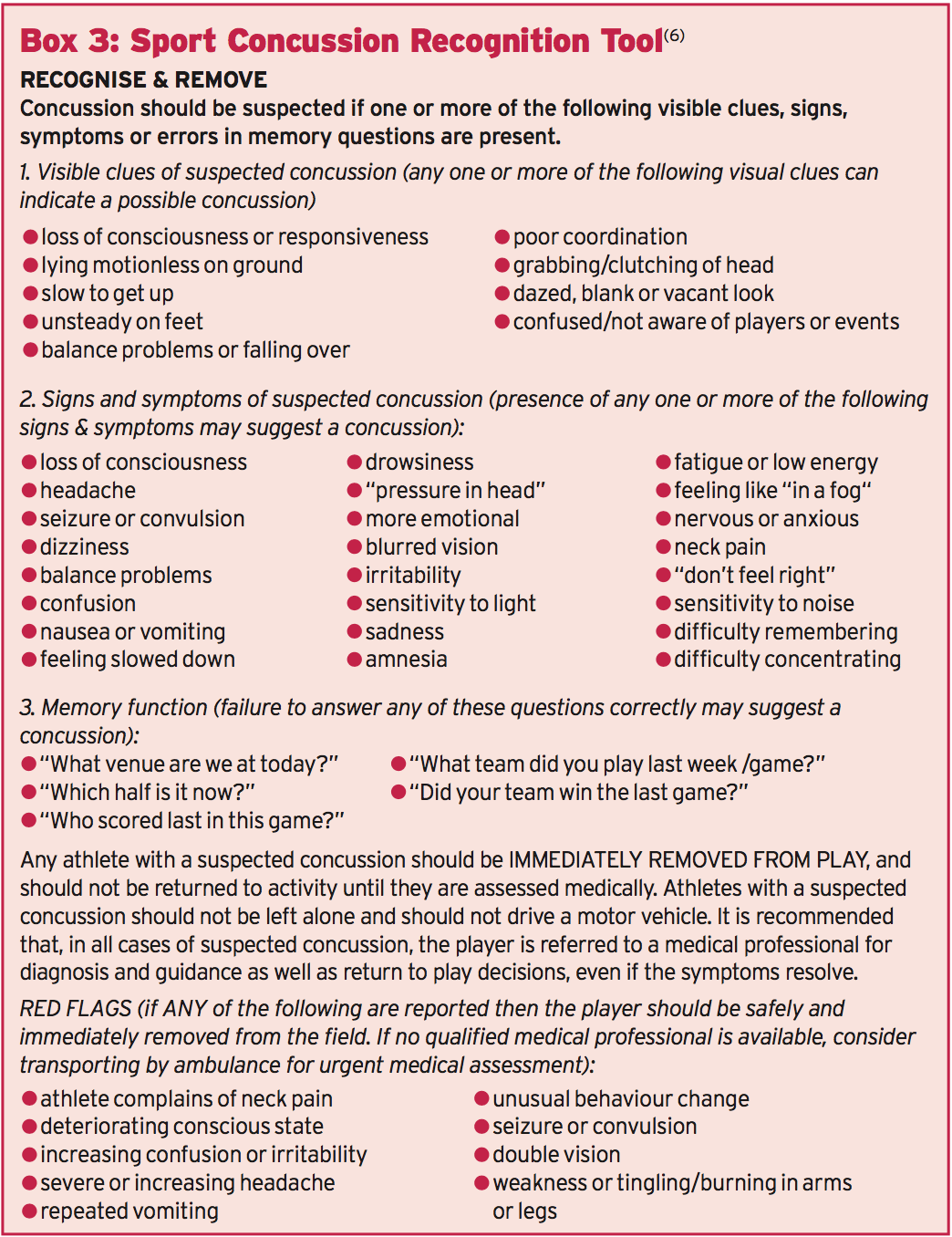

- Concussion symptoms must be resolved before returning to perform with (RTP) and RTP after concussion should happen just with medical clearance from an experienced health-care supplier trained in the analysis and management of concussions — see Box 2. An RTP progression entails a gradual, step-wise increase in bodily demands, sports-specific activities and the danger of contact. If any signs recur using action, the progression ought to be stopped and resumed in the previous symptom-free step. In the brief term, the principal concern with early RTP is diminished reaction time resulting in an increased risk of a repeat concussion or additional injury and prolongation of symptoms. In the long run, there’s a growing concern that head impact exposure and recurrent concussions can contribute to long-term neurological complications and a number of studies have indicated an association between previous concussions and chronic cognitive impairment.

- Physicians should be prepared to offer counseling regarding potential long-term consequences of a concussion and continuing concussions. However, there are currently no evidence-based guidelines for disqualifying/retiring an athlete from a game after a concussion. More commonly, greater efforts are needed to educate involved parties, such as athletes, parents, coaches, officials and school administrators and health care providers to boost concussion recognition, prevention and management.

Recent Findings: On-Field & Same Day Assessment

Make no mistake, but the first assessment of concussion in the mature athlete is tough, given that the elusiveness of harm, the sensitivity and specificity of their sideline assessment tools along with the evolving nature of concussive injury. A very current (2013) review newspaper systematically examined the evidence related to on-field concussion assessment and considered questions related to same day return to play, what to do if no doctor is available onsite, as well as the benefit of distant notification of future concussive events(3). It concluded that the on-field test of sport-related concussion is often a challenge, especially given the elusiveness and variability of presentation, the strain to create a quick diagnosis (as an instance, in the middle of an important match in which the concussed athlete was making a significant contribution), the specificity and sensitivity (or rather lack of) of this on-field assessment tools, along with the dependence on symptom presentation.

However, they cautioned that a range of assessments over a brief time period tend to be necessary and, since signs and symptoms may be postponed, erring on the side of caution (ie maintaining an athlete from participation whenever there’s a distress for harm) is important. In addition, they concluded that although a standardized evaluation of concussion is beneficial in the evaluation of the athlete with suspected concussion, it should NOT take the place of the clinician’s conclusion.

These findings have been very much in agreement with another 2013 review research on instruments currently utilized in the evaluation of sport-related concussion on the day of injury — consequently ‘same day’ assessment tools(4). In this review, a total of 41 research on sports concussion were pooled and their findings analyzed. The authors concluded that several well- supported tests are acceptable to be used in the evaluation of acute concussion from the athletic athletic environment and that these evaluations can provide significant data on the symptoms and functional impairments that clinicians can integrate in their diagnostic formula. But they also cautioned that such tests should not solely be used to diagnose concussion.

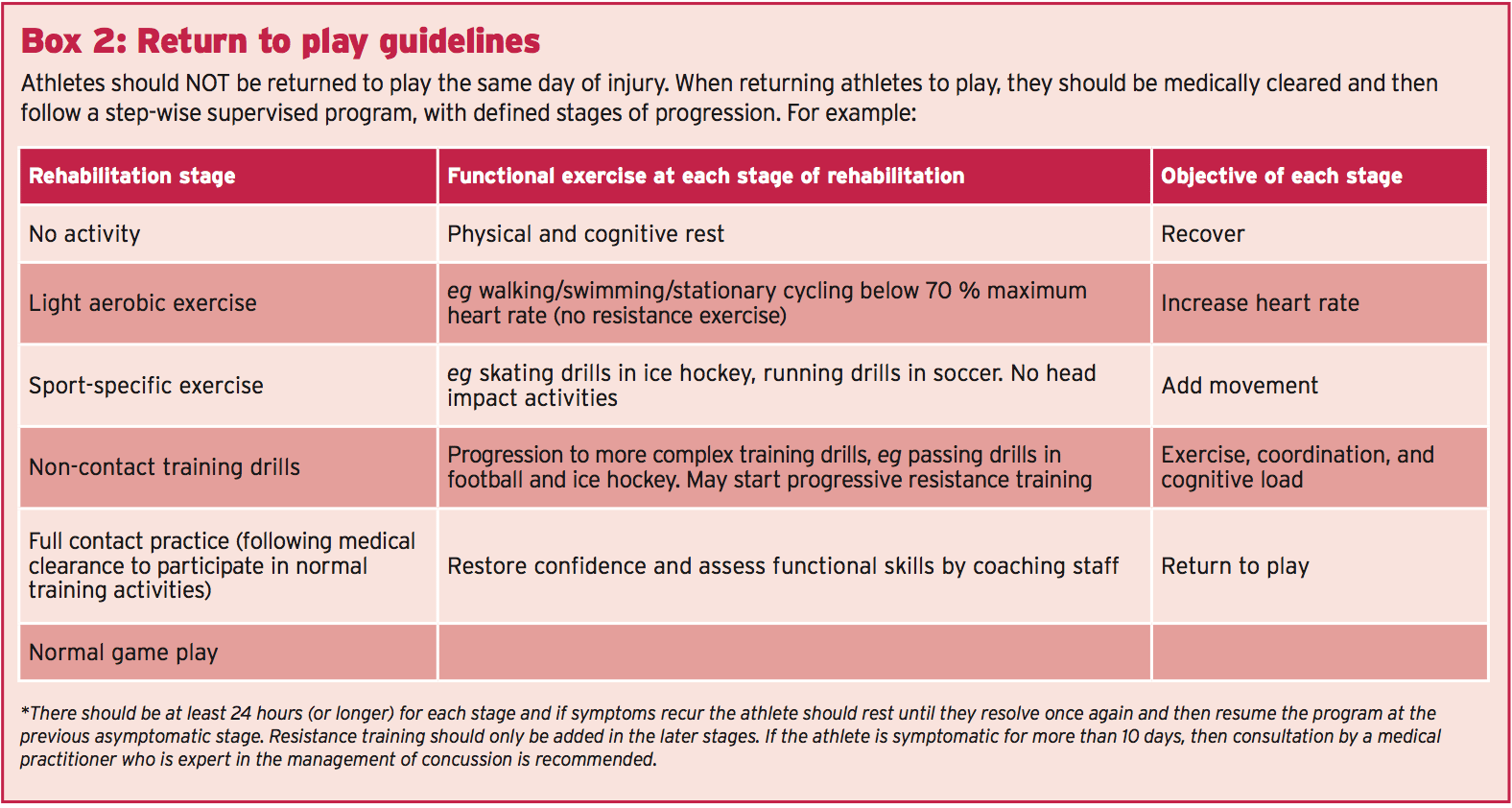

SCAT3 Assessment Tool

As mentioned above, the first evaluation of an injured athlete with suspected concussion remains predominant in determining subsequent action. There are a number of diagnostic tools available, but undoubtedly among the most admired is when there is no one with medical training available to tend to an injured athlete, it is recommended that the ‘Sport Concussion Recognition Tool’ be used instead (seeBox 3). The SCAT3 assessment tool can be downloaded here: http://bjsm. bmj.com/content/47/5/263.full.pdf. The SCAT3 is a standardized instrument for evaluating injured athletes for concussion, and is intended for use by medical professionals. SCAT3 supersedes the first SCAT and SCAT2 published in 2005 and 2009 respectively. Importantly, baseline testing together with the SCAT3 can be beneficial for translating post-injury test scores at a later date. The SCAT3 evaluation tool can be downloaded here: http://bjsm. bmj.com/content/47/5/263.full.pdf

SCAT3 is a detailed tool that assesses the following areas: background, symptom evaluation, cognitive and physical function, neck trauma, balance and coordination. According to the SCAT guidelines, the first indications through a sideline evaluation are critical and any of the following warrants triggering emergency procedures and barbarous transport to the nearest hospital:

SCAT3 is a detailed tool that assesses the following areas: background, symptom evaluation, cognitive and physical function, neck trauma, balance and coordination. According to the SCAT guidelines, the first indications through a sideline evaluation are critical and any of the following warrants triggering emergency procedures and barbarous transport to the nearest hospital:

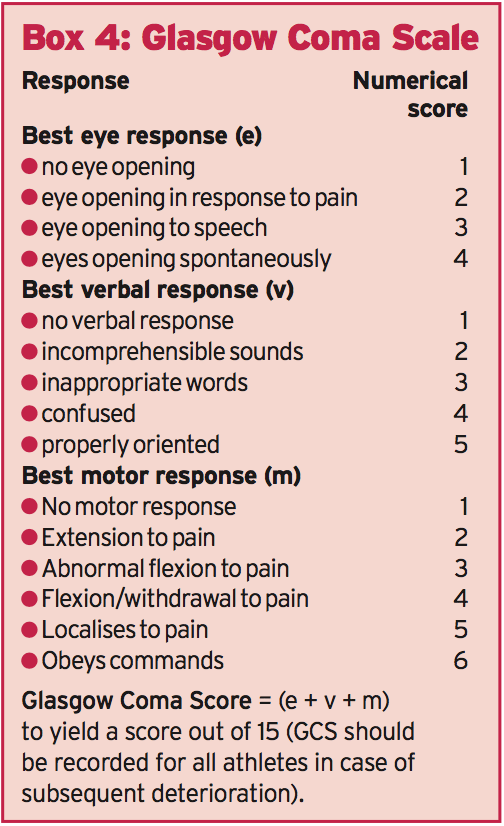

- a Glasgow Coma score of less than 15 (see Box 4)

- deteriorating mental status

- potential spinal injury

- progressive, worsening symptoms or new neurologic signs.

It is important to highlight, but that scoring on the SCAT3 shouldn’t be utilized as a stand-alone process to diagnose concussion, quantify recovery or make conclusions regarding an athlete’s readiness to come back to competition after concussion. Additionally, since signs and symptoms can evolve over time, it’s very important to consider repeat evaluation from the acute evaluation of concussion. Finally, it needs to be stressed that the identification of a concussion is a medical judgment, ideally created by a medical professional. The SCAT3 shouldn’t therefore be used solely to make, or exclude, the diagnosis of concussion in the absence of clinical judgement. An athlete could have a concussion even if their SCAT3 score is ‘normal’.

References

1. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Jan;47(1):15-26. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091941

2. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Apr;40(4):747-55

3. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Apr;47(5):285-8

4. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Apr;47(5):272-84

5. Br J Sports Med 2013 47: 259

6. downloadable from: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/47/5/267.full.pdf

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information herein on "Concussion In Sports: Scientific Research" is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness, Personal Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a Multi-State board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our multidisciplinary team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, and focuses on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of multidisciplinary practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is multidisciplinary, focusing on musculoskeletal and physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for musculoskeletal injuries or disorders.

Our videos, posts, topics, and insights address clinical matters and issues that are directly or indirectly related to our clinical scope of practice.

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies upon request to regulatory boards and the public.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Multidisciplinary Licensing & Board Certifications:

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License #: TX5807, Verified: TX5807

New Mexico DC License #: NM-DC2182, Verified: NM-DC2182

Multi-State Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN*) in Texas & Multi-States

Multi-state Compact APRN License by Endorsement (42 States)

Texas APRN License #: 1191402, Verified: 1191402 *

Florida APRN License #: 11043890, Verified: APRN11043890 *

Colorado License #: C-APN.0105610-C-NP, Verified: C-APN.0105610-C-NP

New York License #: N25929, Verified N25929

License Verification Link: Nursys License Verifier

* Prescriptive Authority Authorized

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Licenses and Board Certifications:

DC: Doctor of Chiropractic

APRNP: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

FNP-BC: Family Practice Specialization (Multi-State Board Certified)

RN: Registered Nurse (Multi-State Compact License)

CFMP: Certified Functional Medicine Provider

MSN-FNP: Master of Science in Family Practice Medicine

MSACP: Master of Science in Advanced Clinical Practice

IFMCP: Institute of Functional Medicine

CCST: Certified Chiropractic Spinal Trauma

ATN: Advanced Translational Neutrogenomics

Memberships & Associations:

TCA: Texas Chiropractic Association: Member ID: 104311

AANP: American Association of Nurse Practitioners: Member ID: 2198960

ANA: American Nurse Association: Member ID: 06458222 (District TX01)

TNA: Texas Nurse Association: Member ID: 06458222

NPI: 1205907805

| Primary Taxonomy | Selected Taxonomy | State | License Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 111N00000X - Chiropractor | NM | DC2182 |

| Yes | 111N00000X - Chiropractor | TX | DC5807 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | TX | 1191402 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | FL | 11043890 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | CO | C-APN.0105610-C-NP |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | NY | N25929 |

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Again, We Welcome You.

Again, We Welcome You.

Comments are closed.