Ankle Injury: Repairing A Chronically Unstable Ankle

In part two of this series, Dr. Alexander Jimenez discusses in detail the surgical options available to stabilize an ankle with chronic instability…

Lateral ankle sprain has a high incidence of occurrence and prevalence amongst the athletic population. In part one of this series, we looked at the natural progression from lateral ankle sprain to chronic ankle instability (CAI) and it was highlighted how after an initial injury, up to 80% of sufferers in high risk sports may end up with long term pain, swelling, dysfunction, and sensations of giving way. The eventual result is CAI(1,2). This suggests that many ankle sprain sufferers will most likely sprain their ankles again, and this may then cascade to late stage CAI.

Although most cases of lateral ankle sprain and subsequent CAI may successfully be treated conservatively through a structured rehabilitation program, this approach may fail, and the athlete is then left with pain, long term dysfunction and instability. In the athletic population, often surgery is advocated in serious first time lateral ankle sprains or if long term CAI develops.

Debate exists in the literature as to whether anatomic repairs are favored over non-anatomic repairs. The argument for anatomic repair versus non-anatomic repair will be discussed here in detail. In the final part of this series next month, the extensive rehabilitation protocol of both anatomic repairs and non-anatomic repairs will be compared and contrasted in detail.

Table of Contents

CAI Management

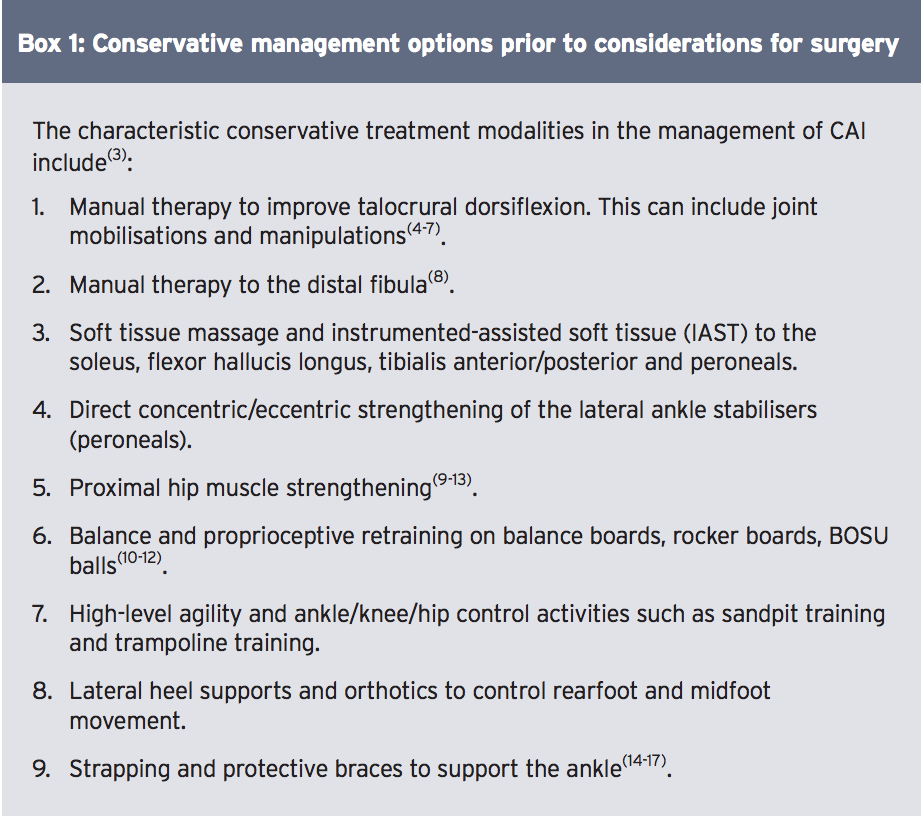

Conservative

It is typical for the sports medicine practitioner to trial a period of conservative management prior to considerations for surgery (see Box 1). Only in extreme cases of gross ligament disruption to both the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) will surgery be immediately advocated.

In a systematic review conducted by Kerkhoffs et al, it was found that early weight bearing with support following acute ankle sprain improved the overall resolution of symptoms associated with a lateral ankle sprain(17). This early weight bearing progression should incorporate an appropriate supportive boot and this may be followed with taping and soft bracing. Several studies have shown that

incorporating early weight bearing and movement improve the return to normal activity, and prevent the development of CAI(17-20).

In part one of this series, we discussed the differences in mechanical instability (gross anatomoical disruption of the ATFL) versus functional instability (balance and proprioceptive dysfunction) of the ankle, and how they can often occur in isolation or in combinations. The reader is therefore directed to issue 163 for a detailed description of the pathogenesis of how an acute ankle sprain leads to CAI.

It is believed that patients with functional instability without demonstrable mechanical instability are more likely to benefit from these non-operative measures mentioned above(21). Surgery is generally reserved for patients with CAI that have failed to improve with a thorough course of conservative management and physical therapy; typically these are the CAI sufferers who exhibit both mechanical and functional instability with episodes of frequent ‘giving way’ of the ankle.

Surgery

If the decisionismade to repairthe acutely sprained ankle ligaments, or if failed conservative management results in CAI, thenthe optionsforsurgery canbe divided into two broad categories:

- Anatomic repair of the lateral-ligament complex.

- Non-anatomic repair, consisting of an ankle reconstruction using tendon weave procedures (tenodesis).

*Anatomic Repairs

The purpose of an anatomic ligament repair is to reconstruct the torn ankle ligaments and capsule to restore the normal ankle anatomy and stability, whilst preserving functional ankle and subtalar joint motion. This can be accomplished with the use of local tissue repair, free tendon graft, or a combination of both. While this type of repair is a technically simpler surgical procedure than non-anatomic reconstruction procedures, its success is dependent on the condition of the injured tissues, and may sometimes require augmentation and/or tenodesis(22,23). In the event of gross ligament disruption with ligament retraction, it may be too difficult for the surgeon to achieve a satisfactory anatomical repair.

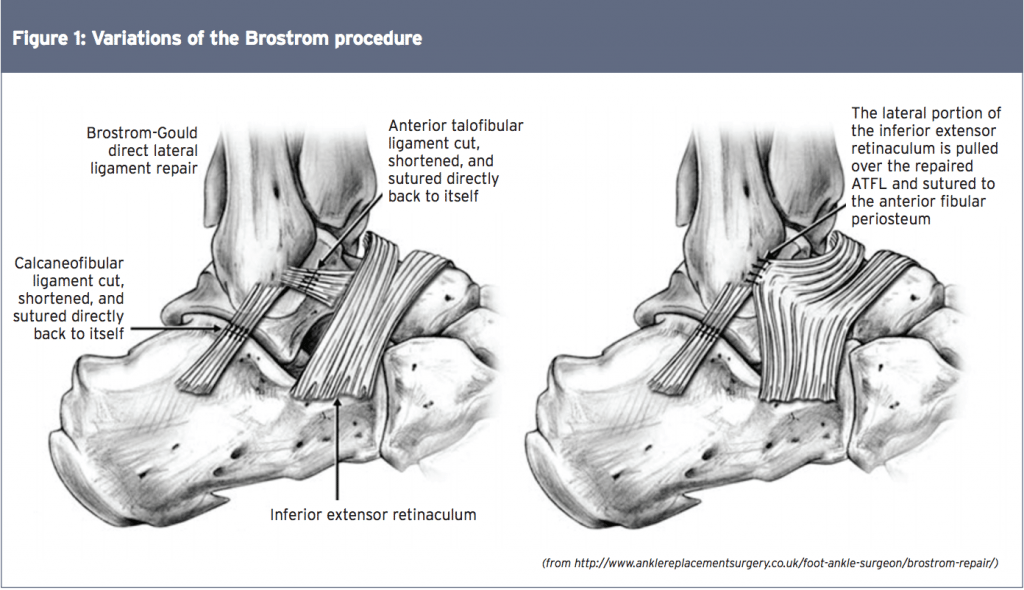

The classic anatomic repair was first described by Brostrom in 1966, who reported on the direct late repair of the lateral ankle ligaments in 60 patients with CAI(24). The torn ends of the ATFL were shortened and repaired directly by mid-substance suturing. In 30% of patients the CFL was also repaired. He reported a success rate of 80% with this technique in terms of return to function and patient satisfaction. As a result of this study, this technique is the foundation of the anatomic repair.

Variations of this original Brostrom procedure include imbrication of the mid-substance of the lateral ligaments, and modiï¬cations in the suturing of the ligaments throughdrill holes in the ï¬bula, with or without reinforcement with ï¬bular periosteum. These include the modified versions by Gould, Karlsson, and the ‘split- Evans’ procedure (see Figure 1)(25-28).

The functional outcomes of anatomic repairs have been excellent; studies report success rates as high as 87% to 95%(24-29). Outcome variables that are typically measured include range of motion of the ankle, strength of the periarticular ankle muscles, return to preinjury activity level, need for reoperation and late stage post- surgical complications.

The benefits of an anatomic repair include the simple surgical approach (and thus a minimisation of tissue disruption and scar tissue formation), the utilisation of local host anatomy while preserving talocrural and subtalar motion, and fewer complications. The most severe complication, although quite rare, is injury to the superï¬cial peroneal or sural nerve.

*Non-Anatomic Repairs

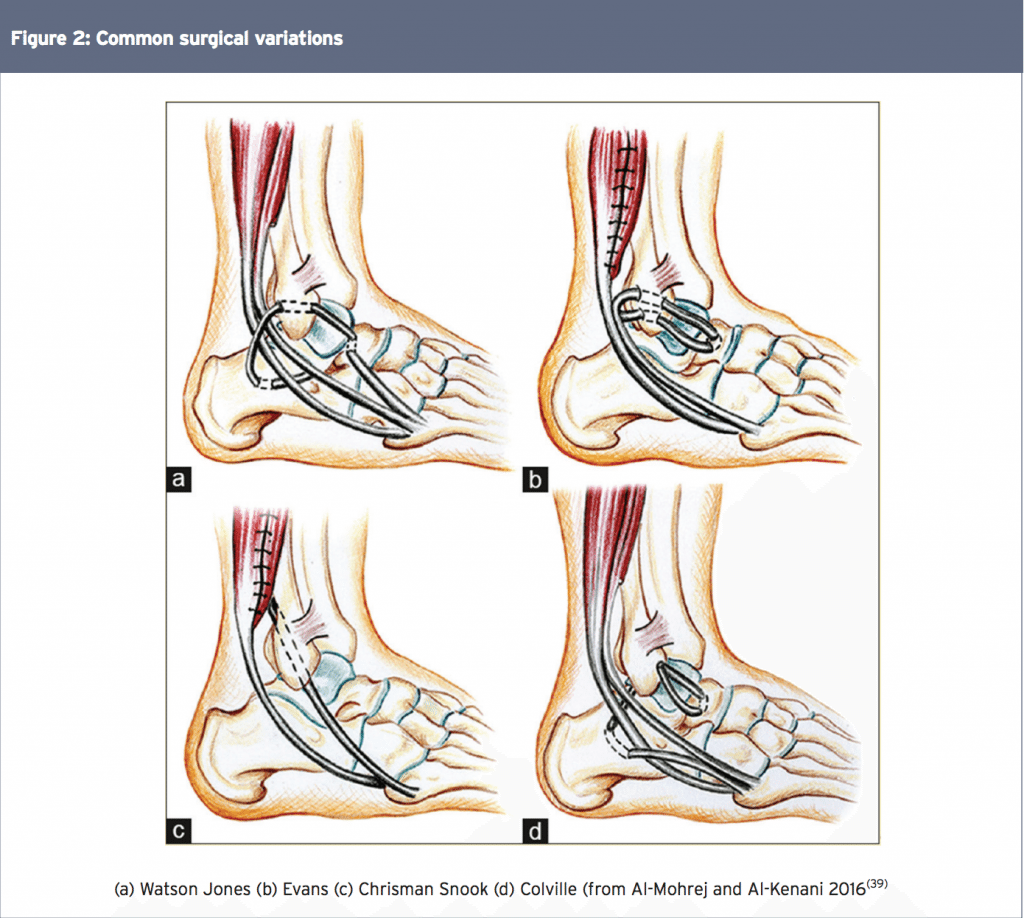

Non-anatomic reconstructions use tendons (tenodesis) orothertypesof graft fixation to stabilisetheankle,alongwiththerepairofthe native ligaments. While multiple variations have been described, most techniques involve rerouting of the peroneus brevis aroundthelateralankle. Themorecommon surgical variations are those developed by Colville, Watson-Jones, Chrisman-Snook and Evans(see Figure 2)(30-36).

The major issue with all of these procedures is that the graft does not follow the orientation of the normal ligaments and therefore it does not adequately support anterior talus movement. As a consequence, the patient may experience subtle anterior ‘sliding’ of the talus, which may be perceived by the patient as the ankle having a ‘slight give’. The long-term consequence of this talar slide is that excessive shear forces are applied to the talocrural joint. This may accelerate erosion of the articular cartilage on the talus and lead to early onset degeneration and osteophyte formation across the anterior joint margin. Furthermore, these procedures lead to a decrease in subtalar and, to a lesser extent, talocrural motion, and the increased risk of adjacent cutaneous nerve injury(37,38).

Comparison Studies

Although initial reports on non-anatomic repairs were promising, comparison studies with longer follow-ups generally favor anatomic repair over non-anatomic reconstructions. A host of studies have been published that compare the long term functional outcomes of anatomic and non-anatomic repairs. Below is a summary of some key findings:

- In a series of comparison studies, including more than 300 patients, with up to 30 years of follow-up data it was found that long-term,non-anatomic tenodesis led to decreased function, increased pain, limited range of motion, instability, increased need for revision procedures, and greater degrees of osteoarthritis compared to anatomic reconstructions(40, 41).

- In a prospective study that compared the modified Broström with the Chrisman-Snook procedure in 40 patients, it was found that both lead to improvement inmore than 80% of patients, although those who underwent a modified Broström procedure had lower rate of complications and better outcomes scores. It was concluded that the modified Broström procedure was superior to the Chrisman-Snook procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability. Inaddition, a greater proportionof complications occurred with the Chrisman-Snook procedure(42)

- Karlssonet al presented the long- term follow-up of patients with lateral ankle instability treated by the Evans procedure(42). Only fifty percent of patients had satisfactory long-term results. Twelve patients with early satisfactory results had deteriorated at 3-6 years. The absence of normal anatomy resulted inrestricted range of motion, reduced long-term stability, and anincreased risk of medial degenerative joint disease of the ankle. They found a larger number of re-operations and less satisfactory overall results.

- This was supported by Kaikkonenet al who also found poor results with the Evans procedure(43). Surgical treatment of chronic ankle instability with the Evans procedure restored the mechanical stability of the joint, but all too frequently, the function of the ankle did not return to the pre-injury level. They found that only 35% of their patients achieved an excellent or good result in performance testing. This finding was primarily due to decreased range of motion, swelling of the ankle, and atrophy of the calf.

- Biomechanically, the modiï¬ed Brostrom procedure was associated with less anterior talar displacement and a decreased talar-tilt angle compared with the Chrisman-Snook procedure(44). The modiï¬ed Brostrom procedure also produced a greater mechanical restraint than either the Evans or Chrisman-Snook procedures(44).

Associated Surgery

When the surgeon decides with the patient that surgical repair of an ankle with CAI is necessary, often the surgeon will also arthroscope the ankle in attempt to identify and fix intra-articular pathology. Komenda et al arthroscopically examined 54 consecutive patients with lateral ankle instability before ligament stabilisation(45). They noted frequent intra-articular pathology, including a 25% incidence of articular chondral injury. The authors concluded that articular cartilage injuries are common in patients with lateral ankle instability, and can be successfully

addressed with ankle arthroscopy in additionto openligament stabilisation.

Advancements in MRI technology may be helpful in identifying associated osteochondral lesions of the talus and peroneal tendon pathology. Its use may be valuable in determining the utility of concomitant arthroscopy, particularly in the presence of mechanical symptoms, chronic ankle pain, or other focal findings onphysical examination.

Summary

Although a large number of acute ankle sprain sufferers will respond to conservative treatment, it is possible that long-term CAI may develop. This may then necessitate surgery to stabilize the ankle and allow a return to function and athletic pursuits. On the balance of evidence, it appears that anatomic repairs are favored over non-anatomic repairs as the normal anatomy of the ankle is preserved and long term outcome studies appear more favorable. In the next issue of SIB, a follow-up article will investigate the extensive rehabilitation protocols of both anatomic repairs and non-anatomic repairs, which will be compared and contrasted in detail.

References

1. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:103–108

2. JAthl Train. 2002;37(4):376–380

3. NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2011; 69: 17-26

4. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(9):417–421

5. Man Ther. 2004;9(2):77–82

6. Phys Ther. 2001;81(4):984–994

7. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(7):464–471

8. Phys Ther Sport. 2015;16(2):135–139

9. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15(6):330–334

10. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9(2):104–109

11. J Sport Rehabil. 2010;19(1):98–114

12. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23(5): 332– 336

13. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):464–470

14. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):575–581

15. Sports Med. 2011;41(3):185–197

16. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(10):653–660

17. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(8):462–471

18. Am J Sports Med. 1994; 22(1):83–88

19. Mil Med. 1994;159(1):20–24

20. Sports Med. 1999;27(1):61–71

21. Foot Ankle Clin 2006; 11: 531-53

22. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998; 6: 368-377

23.Tech Foot Ankle Surg 2005; 4: 98-103

24. Acta Chir Scand. 1966;243:551–565

25. Foot Ankle. 1980;1:84–89

26. JBone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:581–588

27. JBone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:300–303

28. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:268–273

29. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:246–252

30. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:210–213

31. JBone Joint Surg Br 76:610–613

32. Am J Sports Med. 1996. 24:400–404

33. JBone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1–7

34. Clin Orthop. 1981;160:201–211

35. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:594–600

36. Proc R Soc Med 46:343–344

37. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:594–600

38. World J Orthop 6(2): 161-171

39. Avicenna Journal of Medicine. 2016. 6(4), 103- 108

40. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2000; 8: 173-179

41. Foot Ankle Int 2001; 22: 415-421

42. JBone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:476–480

43. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9:239–244

44. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:313–317

45. Foot Ankle Int. 1999. 20(11), 708-713

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information herein on "Chronic Ankle Instability" is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness, Personal Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a Multi-State board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our multidisciplinary team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, and focuses on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of multidisciplinary practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is multidisciplinary, focusing on musculoskeletal and physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for musculoskeletal injuries or disorders.

Our videos, posts, topics, and insights address clinical matters and issues that are directly or indirectly related to our clinical scope of practice.

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies upon request to regulatory boards and the public.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Multidisciplinary Licensing & Board Certifications:

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License #: TX5807, Verified: TX5807

New Mexico DC License #: NM-DC2182, Verified: NM-DC2182

Multi-State Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN*) in Texas & Multi-States

Multi-state Compact APRN License by Endorsement (42 States)

Texas APRN License #: 1191402, Verified: 1191402 *

Florida APRN License #: 11043890, Verified: APRN11043890 *

Colorado License #: C-APN.0105610-C-NP, Verified: C-APN.0105610-C-NP

New York License #: N25929, Verified N25929

License Verification Link: Nursys License Verifier

* Prescriptive Authority Authorized

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Licenses and Board Certifications:

DC: Doctor of Chiropractic

APRNP: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

FNP-BC: Family Practice Specialization (Multi-State Board Certified)

RN: Registered Nurse (Multi-State Compact License)

CFMP: Certified Functional Medicine Provider

MSN-FNP: Master of Science in Family Practice Medicine

MSACP: Master of Science in Advanced Clinical Practice

IFMCP: Institute of Functional Medicine

CCST: Certified Chiropractic Spinal Trauma

ATN: Advanced Translational Neutrogenomics

Memberships & Associations:

TCA: Texas Chiropractic Association: Member ID: 104311

AANP: American Association of Nurse Practitioners: Member ID: 2198960

ANA: American Nurse Association: Member ID: 06458222 (District TX01)

TNA: Texas Nurse Association: Member ID: 06458222

NPI: 1205907805

| Primary Taxonomy | Selected Taxonomy | State | License Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 111N00000X - Chiropractor | NM | DC2182 |

| Yes | 111N00000X - Chiropractor | TX | DC5807 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | TX | 1191402 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | FL | 11043890 |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | CO | C-APN.0105610-C-NP |

| Yes | 363LF0000X - Nurse Practitioner - Family | NY | N25929 |

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Again, We Welcome You.

Again, We Welcome You.

Comments are closed.